So I just learned about the volatile keyword while writing some examples for a section that I am TAing tomorrow. I wrote a quick program to demonstrate that the ++ and -- operations are not atomic.

public class Q3 {

private static int count = 0;

private static class Worker1 implements Runnable{

public void run(){

for(int i = 0; i < 10000; i++)

count++; //Inner class maintains an implicit reference to 开发者_开发技巧its parent

}

}

private static class Worker2 implements Runnable{

public void run(){

for(int i = 0; i < 10000; i++)

count--; //Inner class maintains an implicit reference to its parent

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

while(true){

Thread T1 = new Thread(new Worker1());

Thread T2 = new Thread(new Worker2());

T1.start();

T2.start();

T1.join();

T2.join();

System.out.println(count);

count = 0;

Thread.sleep(500);

}

}

}

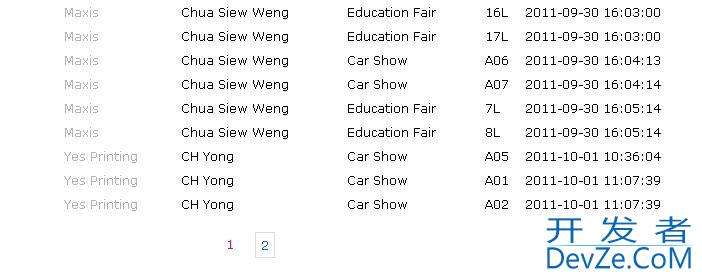

As expected the output of this program is generally along the lines of:

-1521

-39

0

0

0

0

0

0

However, when I change:

private static int count = 0;

to

private static volatile int count = 0;

my output changes to:

0

3077

1

-3365

-1

-2

2144

3

0

-1

1

-2

6

1

1

I've read When exactly do you use the volatile keyword in Java? so I feel like I've got a basic understanding of what the keyword does (maintain synchronization across cached copies of a variable in different threads but is not read-update-write safe). I understand that this code is, of course, not thread safe. It is specifically not thread-safe to act as an example to my students. However, I am curious as to why adding the volatile keyword makes the output not as "stable" as when the keyword is not present.

Why does marking a Java variable volatile make things less synchronized?

The question "why does the code run worse" with the volatile keyword is not a valid question. It is behaving differently because of the different memory model that is used for volatile fields. The fact that your program's output tended towards 0 without the keyword cannot be relied upon and if you moved to a different architecture with differing CPU threading or number of CPUs, vastly different results would not be uncommon.

Also, it is important to remember that although x++ seems atomic, it is actually a read/modify/write operation. If you run your test program on a number of different architectures, you will find different results because how the JVM implements volatile is very hardware dependent. Accessing volatile fields can also be significantly slower than accessing cached fields -- sometimes by 1 or 2 orders of magnitude which will change the timing of your program.

Use of the volatile keyword does erect a memory barrier for the specific field and (as of Java 5) this memory barrier is extended to all other shared variables. This means that the value of the variables will be copied in/out of central storage when accessed. However, there are subtle differences between volatile and the synchronized keyword in Java. For example, there is no locking happening with volatile so if multiple threads are updating a volatile variable, race conditions will exist around non-atomic operations. That's why we use AtomicInteger and friends which take care of increment functions appropriately without synchronization.

Here's some good reading on the subject:

- Java theory and practice: Managing volatility

- The volatile keyword in Java

Hope this helps.

An educated guess at what you're seeing - when not marked as volatile the JIT compiler is using the x86 inc/dec operations which can update the variable atomically. Once marked volatile these operations are no longer used and the variable is instead read, incremented/decremented, and then finally written causing more "errors".

The non-volatile setup has no guarantees it'll function well though - on a different architecture it could be worse than when marked volatile. Marking the field volatile does not begin to solve any of the race issues present here.

One solution would be to use the AtomicInteger class, which does allow atomic increments/decrements.

Volatile variables act as if each interaction is enclosed in a synchronized block. As you mentioned, increment and decrement is not atomic, meaning each increment and decrement contains two synchronized regions (the read and the write). I suspect that the addition of these pseudolocks is increasing the chance that the operations conflict.

In general the two threads would have a random offset from another, meaning that the likelihood of either one overwriting the other is even. But the synchronization imposed by volatile may be forcing them to be in inverse-lockstep, which, if they mesh together the wrong way, increases the chance of a missed increment or decrement. Further, once they get in this lockstep, the synchronization makes it less likely that they will break out of it, increasing the deviation.

I stumbled upon this question and after playing with the code for a little bit found a very simple answer.

After initial warm up and optimizations (the first 2 numbers before the zeros) when the JVM is working at full speed T1 simply starts and finishes before T2 even starts, so count is going all the way up to 10000 and then to 0.

When I changed the number of iterations in the worker threads from 10000 to 100000000 the output is very unstable and different every time.

The reason for the unstable output when adding volatile is that it makes the code much slower and even with 10000 iterations T2 has enough time to start and interfere with T1.

The reason for all those zeroes is not that the ++'s and --'s are balancing each other out. The reason is that there is nothing here to cause count in the looping threads to affect count in the main thread. You need synch blocks or a volatile count (a "memory barrier) to force the JVM to make everything see the same value. With your particular JVM/hardware, what is most likely happening that the value is kept in a register at all times and never getting to cache--let alone main memory--at all.

In the second case you are doing what you intended: non-atomic increments and decrements on the same course and getting results something like what you expected.

This is an ancient question, but something needed to be said about each thread keeping it's own, independent copy of the data.

If you see a value of count that is not a multiple of 10000, it just shows that you have a poor optimiser.

It doesn't 'make things less synchronized'. It makes them more synchronized, in that threads will always 'see' an up to date value for the variable. This requires erection of memory barriers, which have a time cost.

![Interactive visualization of a graph in python [closed]](https://www.devze.com/res/2023/04-10/09/92d32fe8c0d22fb96bd6f6e8b7d1f457.gif)

加载中,请稍侯......

加载中,请稍侯......

精彩评论