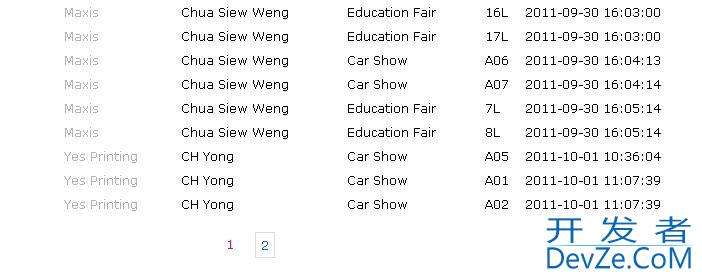

Let's say I am writing an API, and one of my functions take a parameter that represents a channel, and will only ever be between the values 0 and 15. I could write it like this:

void Func(unsigned char channel)

{

if(channel < 0 || channel > 15)

{ // throw some exception }

// do something

}

Or do I take advantage of C++ being a strongly typed language, and make myself a type:

class CChannel

{

public:

CChannel(unsigned char value) : m_Value(value)

{

if(channel < 0 || channel > 15)

{ // throw some exception }

}

operator unsigned char() { return m_Value; }

private:

unsigned char m_Value;

}

My function now becom开发者_开发百科es this:

void Func(const CChannel &channel)

{

// No input checking required

// do something

}

But is this total overkill? I like the self-documentation and the guarantee it is what it says it is, but is it worth paying the construction and destruction of such an object, let alone all the additional typing? Please let me know your comments and alternatives.

If you wanted this simpler approach generalize it so you can get more use out of it, instead of tailor it to a specific thing. Then the question is not "should I make a entire new class for this specific thing?" but "should I use my utilities?"; the latter is always yes. And utilities are always helpful.

So make something like:

template <typename T>

void check_range(const T& pX, const T& pMin, const T& pMax)

{

if (pX < pMin || pX > pMax)

throw std::out_of_range("check_range failed"); // or something else

}

Now you've already got this nice utility for checking ranges. Your code, even without the channel type, can already be made cleaner by using it. You can go further:

template <typename T, T Min, T Max>

class ranged_value

{

public:

typedef T value_type;

static const value_type minimum = Min;

static const value_type maximum = Max;

ranged_value(const value_type& pValue = value_type()) :

mValue(pValue)

{

check_range(mValue, minimum, maximum);

}

const value_type& value(void) const

{

return mValue;

}

// arguably dangerous

operator const value_type&(void) const

{

return mValue;

}

private:

value_type mValue;

};

Now you've got a nice utility, and can just do:

typedef ranged_value<unsigned char, 0, 15> channel;

void foo(const channel& pChannel);

And it's re-usable in other scenarios. Just stick it all in a "checked_ranges.hpp" file and use it whenever you need. It's never bad to make abstractions, and having utilities around isn't harmful.

Also, never worry about overhead. Creating a class simply consists of running the same code you would do anyway. Additionally, clean code is to be preferred over anything else; performance is a last concern. Once you're done, then you can get a profiler to measure (not guess) where the slow parts are.

Yes, the idea is worthwhile, but (IMO) writing a complete, separate class for each range of integers is kind of pointless. I've run into enough situations that call for limited range integers that I've written a template for the purpose:

template <class T, T lower, T upper>

class bounded {

T val;

void assure_range(T v) {

if ( v < lower || upper <= v)

throw std::range_error("Value out of range");

}

public:

bounded &operator=(T v) {

assure_range(v);

val = v;

return *this;

}

bounded(T const &v=T()) {

assure_range(v);

val = v;

}

operator T() { return val; }

};

Using it would be something like:

bounded<unsigned, 0, 16> channel;

Of course, you can get more elaborate than this, but this simple one still handles about 90% of situations pretty well.

No, it is not overkill - you should always try to represent abstractions as classes. There are a zillion reasons for doing this and the overhead is minimal. I would call the class Channel though, not CChannel.

Can't believe nobody mentioned enum's so far. Won't give you a bulletproof protection, but still better than a plain integer datatype.

Looks like overkill, especially the operator unsigned char() accessor. You're not encapsulating data, you're making evident things more complicated and, probably, more error-prone.

Data types like your Channel are usually a part of something more abstracted.

So, if you use that type in your ChannelSwitcher class, you could use commented typedef right in the ChannelSwitcher's body (and, probably, your typedef is going to be public).

// Currently used channel type

typedef unsigned char Channel;

Whether you throw an exception when constructing your "CChannel" object or at the entrance to the method that requires the constraint makes little difference. In either case you're making runtime assertions, which means the type system really isn't doing you any good, is it?

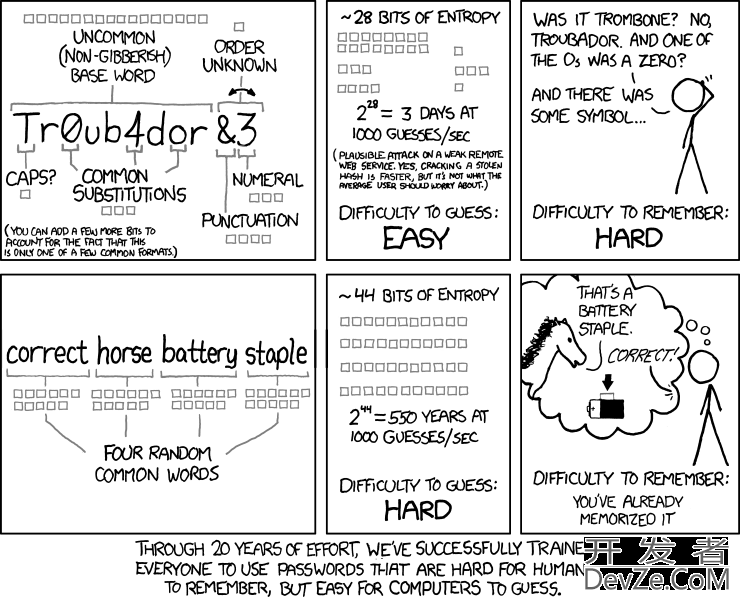

If you want to know how far you can go with a strongly typed language, the answer is "very far, but not with C++." The kind of power you need to statically enforce a constraint like, "this method may only be invoked with a number between 0 and 15" requires something called dependent types--that is, types which depend on values.

To put the concept into pseudo-C++ syntax (pretending C++ had dependent types), you might write this:

void Func(unsigned char channel, IsBetween<0, channel, 15> proof) {

...

}

Note that IsBetween is parameterized by values rather than types. In order to call this function in your program now, you must provide to the compiler the second argument, proof, which must have the type IsBetween<0, channel, 15>. Which is to say, you have to prove at compile-time that channel is between 0 and 15! This idea of types which represent propositions, whose values are proofs of those propositions, is called the Curry-Howard Correspondence.

Of course, proving such things can be difficult. Depending on your problem domain, the cost/benefit ratio can easily tip in favor of just slapping runtime checks on your code.

Whether something is overkill or not often depends on lots of different factors. What might be overkill in one situation might not in another.

This case might not be overkill if you had lots of different functions that all accepted channels and all had to do the same range checking. The Channel class would avoid code duplication, and also improve readability of the functions (as would naming the class Channel instead of CChannel - Neil B. is right).

Sometimes when the range is small enough I will instead define an enum for the input.

If you add constants for the 16 different channels, and also a static method that fetches the channel for a given value (or throws an exception if out of range) then this can work without any additional overhead of object creation per method call.

Without knowing how this code is going to be used, it's hard to say if it's overkill or not or pleasant to use. Try it out yourself - write a few test cases using both approaches of a char and a typesafe class - and see which you like. If you get sick of it after writing a few test cases, then it's probably best avoided, but if you find yourself liking the approach, then it might be a keeper.

If this is an API that's going to be used by many, then perhaps opening it up to some review might give you valuable feedback, since they presumably know the API domain quite well.

In my opinion, I don't think what you are proposing is a big overhead, but for me, I prefer to save the typing and just put in the documentation that anything outside of 0..15 is undefined and use an assert() in the function to catch errors for debug builds. I don't think the added complexity offers much more protection for programmers who are already used to C++ language programming which contains alot of undefined behaviours in its specs.

You have to make a choice. There is no silver bullet here.

Performance

From the performance perspective, the overhead isn't going to be much if at all. (unless you've got to counting cpu cycles) So most likely this shouldn't be the determining factor.

Simplicity/ease of use etc

Make the API simple and easy to understand/learn. You should know/decide whether numbers/enums/class would be easier for the api user

Maintainability

If you are very sure the channel type is going to be an integer in the foreseeable future , I would go without the abstraction (consider using enums)

If you have a lot of use cases for a bounded values, consider using the templates (Jerry)

- If you think, Channel can potentially have methods make it a class right now.

Coding effort Its a one time thing. So always think maintenance.

The channel example is a tough one:

At first it looks like a simple limited-range integer type, like you find in Pascal and Ada. C++ gives you no way to say this, but an enum is good enough.

If you look closer, could it be one of those design decisions that are likely to change? Could you start referring to "channel" by frequency? By call letters (WGBH, come in)? By network?

A lot depends on your plans. What's the main goal of the API? What's the cost model? Will channels be created very frequently (I suspect not)?

To get a slightly different perspective, let's look at the cost of screwing up:

You expose the rep as

int. Clients write a lot of code, the interface is either respected or your library halts with an assertion failure. Creating channels is dirt cheap. But if you need to change the way you're doing things, you lose "backward bug-compatibility" and annoy authors of sloppy clients.You keep it abstract. Everybody has to use the abstraction (not so bad), and everybody is futureproofed against changes in the API. Maintaining backwards compatibility is a piece of cake. But creating channels is more costly, and worse, the API has to state carefully when it is safe to destroy a channel and who is responsible for the decision and the destruction. Worse case scenario is that creating/destroying channels leads to a big memory leak or other performance failure—in which case you fall back to the enum.

I'm a sloppy programmer, and if it were for my own work, I'd go with the enum and eat the cost if the design decision changes down the line. But if this API were to go out to a lot of other programmers as clients, I'd use the abstraction.

Evidently I'm a moral relativist.

An integer with values only ever between 0 and 15 is an unsigned 4-bit integer (or half-byte, nibble. I imagine if this channel switching logic would be implemented in hardware, then the channel number might be represented as that, a 4-bit register). If C++ had that as a type you would be done right there:

void Func(unsigned nibble channel)

{

// do something

}

Alas, unfortunately it doesn't. You could relax the API specification to express that the channel number is given as an unsigned char, with the actual channel being computed using a modulo 16 operation:

void Func(unsigned char channel)

{

channel &= 0x0f; // truncate

// do something

}

Or, use a bitfield:

#include <iostream>

struct Channel {

// 4-bit unsigned field

unsigned int n : 4;

};

void Func(Channel channel)

{

// do something with channel.n

}

int main()

{

Channel channel = {9};

std::cout << "channel is" << channel.n << '\n';

Func (channel);

}

The latter might be less efficient.

I vote for your first approach, because it's simpler and easier to understand, maintain, and extend, and because it is more likely to map directly to other languages should your API have to be reimplemented/translated/ported/etc.

This is abstraction my friend! It's always neater to work with objects

![Interactive visualization of a graph in python [closed]](https://www.devze.com/res/2023/04-10/09/92d32fe8c0d22fb96bd6f6e8b7d1f457.gif)

加载中,请稍侯......

加载中,请稍侯......

精彩评论