Want to improve this question? Update the question so it can be answered with facts and citations by editing this post.

Closed 9 years ago.

Improve this questionAs far as I can see, the usual (and best in my opinion) order for teaching iterting constructs in functional programming with Scheme is to first teach recursion and maybe later get into things like map, reduce and all SRFI-1 procedures. This is probably, I guess, because with recursion the student has everything that's necessary for iterating (and even re-write all of SRFI-1 if he/she wants to do so).

Now I was wondering if the opposite approach has ever been tried: use several procedures from SRFI-1 and only when they are not enough (for example, to approximate a function) use recursion. My guess is that the result would not be good, but I'd like to know about any past experiences with this approach.

Of course, this is not specific to Scheme; the question is also valid for any functional language.

One book that teaches "applicative programming" (the use of combinators) before recursion is Dave Touretsky's COMMON LISP: A Gentle Introduction to Symbolic Computation -- but then, it's a Common Lisp book, and he can teach imperative looping before that.

IMO starting with basic blocks of knowledge first is better, then derive the results. This is what they do in mathematics, i.e. they don't introduce exponentiation before multiplication, and multiplication before addition because the former in each case is derived from the latter. I have seen some instructors go the other way around, and I believe it is not as successful like when you go from the basics to the results. In addition, by delaying the more advanced topics, you give students a mental challenge to derive these results them selves using the knowledge they already have.

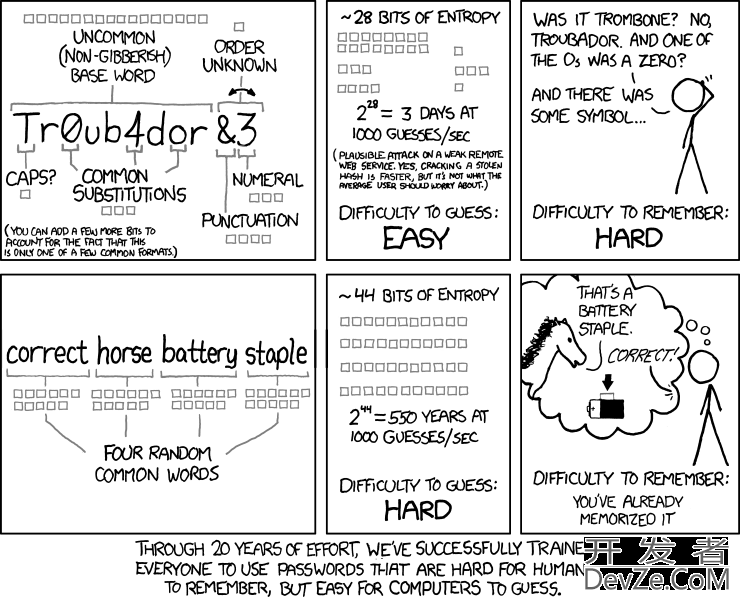

There is something fundamentally flawed in saying "with recursion the student has everything that's necessary for iterating". It's true that when you know how to write (recursive) functions you can do anything, but what is that better for a student? When you think about it, you also have everything you need if you know machine language, or to make a more extreme point, if I give you a cpu and a pile of wires.

Yes, that's an over-exaggeration, but it can relate to the way people teach. Take any language and remove any inessential constructs -- at the extreme of doing so in a functional language like Scheme, you'll be left with the lambda calculus (or something similar), which -- again -- is everything that you need. But obviously you shouldn't throw beginners into that pot before you cover more territory.

To put this in more concrete perspective, consider the difference between a list and a pair, as they are implemented in Scheme. You can do a lot with just lists even if you know nothing about how they're implemented as pairs. In fact, if you give students a limited form of cons that requires a proper list as its second argument then you'll be doing them a favor by introducing a consistent easier-to-grok concept before you proceed to the details of how lists are implemented. If you have experience teaching this stuff, then I'm sure that you've encountered many students that get hopelessly confused over using cons where the want append and vice versa. Problems that require both can be extremely difficult to newbies, and all the box+pointer diagrams in the world are not going to help them.

So, to give an actual suggestion, I recommend you have a look at HtDP: one of the things that this book is doing very carefully is to expose students gradually to programming, making sure that the mental picture at every step is consistent with what the student knows at that point.

I have never seen this order used in teaching, and I find it as backwards as you. There are quite a few questions on StackOverflow that show that at least some programmers think "functional programming" is exclusively the application of "magic" combinators and are at a loss when the combinator they need doesn't exist, even if what they would need is as simple as map3.

Considering this bias, I would make sure that students are able to write each combinator themselves before introducing it.

I also think introducing map/reduce before recursion is a good idea. (However, the classic SICP introduces recursion first, and implement map/reduce based on list and recursion. This is a building abstraction from bottom up approach. Its emphises is still abstraction.)

Here's the sum-of-squares example I can share with you using F#/ML:

let sumOfSqrs1 lst =

let rec sum lst acc =

match lst with

| x::xs -> sum xs (acc + x * x)

| [] -> acc

sum lst 0

let sumOfSqr2 lst =

let sqr x = x * x

lst |> List.map sqr |> List.sum

The second method is a more abstract way to do this sum-of-squares problem, while the first one expresses too much details. The strength of functional programming is better abstraction. The second program using the List library expresses the idea that the for loop can be abstracted out.

Once the student could play with List.*, they would be eager to know how these functions are implemented. At that time, you could go back to recursion. This is kind of top-down teaching approach.

I think this is a bad idea.

Recursion is one of the hardest basic subjects in programming to understand, and even harder to use. The only way to learn this is to do it, and a lot of it.

If the students will be handed the nicely abstracted higher order functions, they will use these over recursion, and will just use the higher order functions. Then when they will need to write a higher order function themselves, they will be clueless and will need you, the teacher, to practically write the code for them.

As someone mentioned, you've gotta learn a subject bottom-up if you want people to really understand a subject and how to customize it to their needs.

I find that a lot of people when programming functionally often 'imitate' an imperative style and try to imitate loops with recursion when they don't need anything resembling a loop and need map or fold/reduce instead.

Most functional programmers would agree that you shouldn't try to imitate an imperative style, I think recursion shouldn't be 'taught' at all, but should develop naturally and self-explanatory, in declarative programming it's often at various points evident that a function is defined in terms of itself. Recursion shouldn't be seen as 'looping' but as 'defining a function in terms of itself'.

Map however is a repetition of the same thing all over again, often when people use (tail) recursion to simulate loops, they should be using map in functional style.

The thing is that the "recursion" you really want to teach/learn is, ultimately, tail recursion, which is technically not recursion but a loop.

So I say go ahead and teach/learn the real recursion (the one nobody uses in real-life because it's impractical), then teach why they are useless, then teach tail-recursion, then teach why they are not recursions.

That seems to me to be the best way. If you're learning, do all this before using higher-order functions too much. If you're teaching, show them how they replace loops (and then they'll understand later when you teach tail-recursion how the looping is really just hidden but still there).

![Interactive visualization of a graph in python [closed]](https://www.devze.com/res/2023/04-10/09/92d32fe8c0d22fb96bd6f6e8b7d1f457.gif)

加载中,请稍侯......

加载中,请稍侯......

精彩评论