Let's say I have this code:

my_dict = {}

default_value = {'surname': '', 'age': 0}

# get info about john, or a default dict

item = my_dict.get('john', default_value)

# edit the data

item[surname] = 'smith'

item[age] = 68

my_dict['john'] = item

The problem becomes clear, i开发者_开发问答f we now check the value of default_value:

>>> default_value

{'age': 68, 'surname': 'smith'}

It is obvious, that my_dict.get() did not return the value of default_value, but a pointer (?) to it.

The problem could be worked around by changing the code to:

item = my_dict.get('john', {'surname': '', 'age': 0})

but that doesn't seem to be a nice way to do it. Any ideas, comments?

item = my_dict.get('john', default_value.copy())

You're always passing a reference in Python.

This doesn't matter for immutable objects like str, int, tuple, etc. since you can't change them, only point a name at a different object, but it does for mutable objects like list, set, and dict. You need to get used to this and always keep it in mind.

Edit: Zach Bloom and Jonathan Sternberg both point out methods you can use to avoid the call to copy on every lookup. You should use either the defaultdict method, something like Jonathan's first method, or:

def my_dict_get(key):

try:

item = my_dict[key]

except KeyError:

item = default_value.copy()

This will be faster than if when the key nearly always already exists in my_dict, if the dict is large. You don't have to wrap it in a function but you probably don't want those four lines every time you access my_dict.

See Jonathan's answer for timings with a small dict. The get method performs poorly at all sizes I tested, but the try method does better at large sizes.

Don't use get. You could do:

item = my_dict.get('john', default_value.copy())

But this requires a dictionary to be copied even if the dictionary entry exists. Instead, consider just checking if the value is there.

item = my_dict['john'] if 'john' in my_dict else default_value.copy()

The only problem with this is that it will perform two lookups for 'john' instead of just one. If you're willing to use an extra line (and None is not a possible value you could get from the dictionary), you could do:

item = my_dict.get('john')

if item is None:

item = default_value.copy()

EDIT: I thought I'd do some speed comparisons with timeit. The default_value and my_dict were globals. I did them each for both if the key was there, and if there was a miss.

Using exceptions:

def my_dict_get():

try:

item = my_dict['key']

except KeyError:

item = default_value.copy()

# key present: 0.4179

# key absent: 3.3799

Using get and checking if it's None.

def my_dict_get():

item = my_dict.get('key')

if item is None:

item = default_value.copy()

# key present: 0.57189

# key absent: 0.96691

Checking its existance with the special if/else syntax

def my_dict_get():

item = my_dict['key'] if 'key' in my_dict else default_value.copy()

# key present: 0.39721

# key absent: 0.43474

Naively copying the dictionary.

def my_dict_get():

item = my_dict.get('key', default_value.copy())

# key present: 0.52303 (this may be lower than it should be as the dictionary I used was one element)

# key absent: 0.66045

For the most part, everything except the one using exceptions are very similar. The special if/else syntax seems to have the lowest time for some reason (no idea why).

In Python dicts are both objects (so they are always passed as references) and mutable (meaning they can be changed without being recreated).

You can copy your dictionary each time you use it:

my_dict.get('john', default_value.copy())

You can also use the defaultdict collection:

from collections import defaultdict

def factory():

return {'surname': '', 'age': 0}

my_dict = defaultdict(factory)

my_dict['john']

The main thing to realize is that everything in Python is pass-by-reference. A variable name in a C-style language is usually shorthand for an object-shaped area of memory, and assigning to that variable makes a copy of another object-shaped area... in Python, variables are just keys in a dictionary (locals()), and the act of assignment just stores a new reference. (Technically, everything is a pointer, but that's an implementation detail).

This has a number of implications, the main one being there will never be an implicit copy of an object made because you passed it to a function, assigned it, etc. The only way to get a copy is to explicitly do so. The python stdlib offers a copy module which contains some things, including a copy() and deepcopy() function for when you want to explicitly make a copy of something. Also, some types expose a .copy() function of their own, but this is not a standard, or consistently implemented. Others which are immutable tend to sometimes offer a .replace() method, which makes a mutated copy.

In the case of your code, passing in the original instance obviously doesn't work, and making a copy ahead of time (when you may not need to) is wasteful. So the simplest solution is probably...

item = my_dict.get('john')

if item is None:

item = default_dict.copy()

It would be useful in this case if .get() supported passing in a default value constructor function, but that's probably over-engineering a base class for a border case.

because my_dict.get('john', default_value.copy()) would create a copy of default dict each time get is called (even when 'john' is present and returned), it is faster and very OK to use this try/except option:

try:

return my_dict['john']

except KeyError:

return {'surname': '', 'age': 0}

Alternatively, you can also use a defaultdict:

import collections

def default_factory():

return {'surname': '', 'age': 0}

my_dict = collections.defaultdict(default_factory)

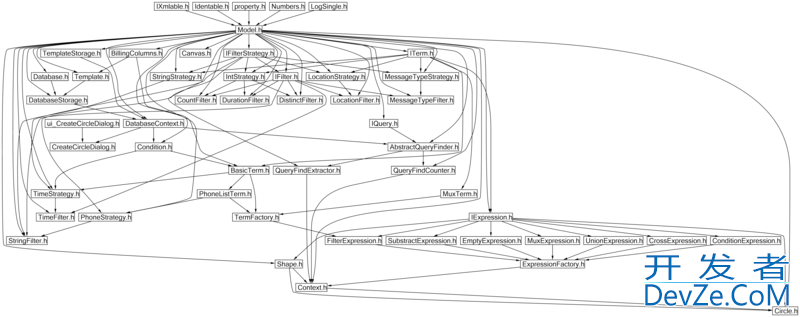

![Interactive visualization of a graph in python [closed]](https://www.devze.com/res/2023/04-10/09/92d32fe8c0d22fb96bd6f6e8b7d1f457.gif)

加载中,请稍侯......

加载中,请稍侯......

精彩评论