A few years back, researchers announced that they had completed a brute-force comprehensive solution to checkers.

I have been interested in another similar game that should have fewer states, but is still quite impractical to run a complete solver on in any reasonable time frame. I would still like to make an attempt, as even a partial solution could give valuable information.

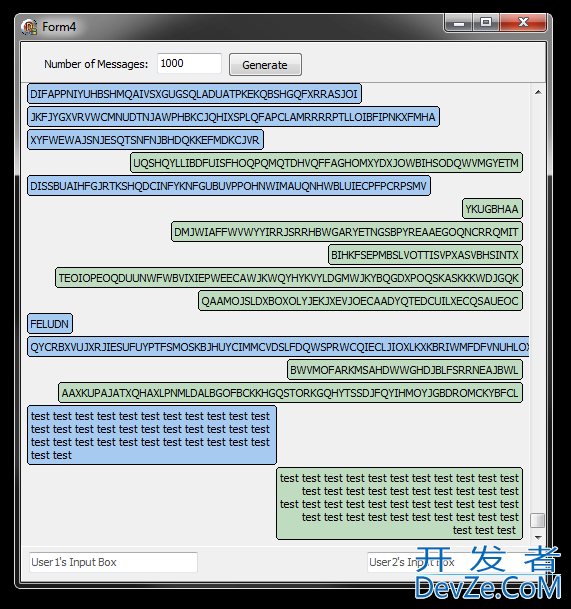

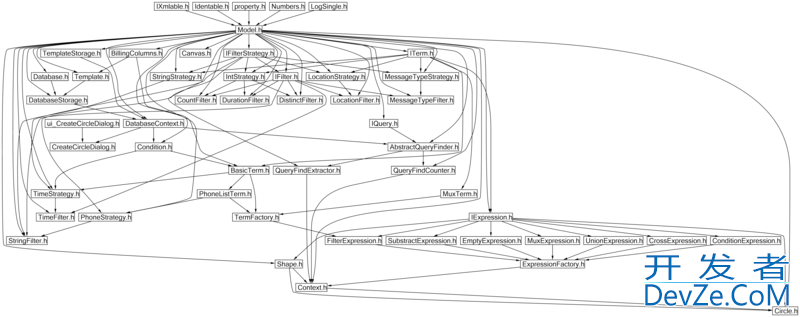

Conceptually I would like to have a database of game states that has every known position, as well as its succeeding positions. One or more clients can grab unexplored states from the database, calculate possible moves, and insert the new states into the database. Once an endgame state is found, all states leading up to it can be updated with the minimax information to build a decision trees. If intelligent decisions are made to pick probable branches to explore, I can build information for the most important branches, and then gradually build up to completion over time.

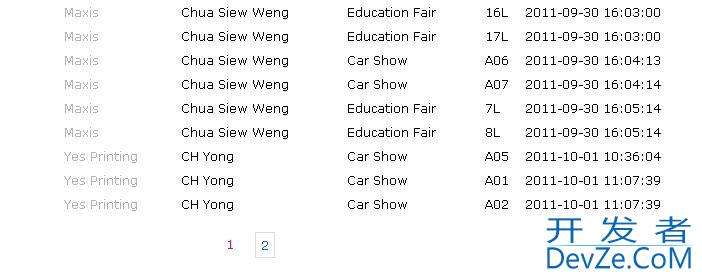

Ignoring the merits of this idea, or the feasability of it, what is the best way to implement such a database? I made a quick prototype in sql server that stored a string representation of each state. It worked, but my solver client ran very very slow, as it puled out one state at a time and calculated all moves. I feel like I need to do larger chunks in memory, but the search space is definitely too large to store it all in memory at once.

Is there a database system better suited to this kind of job? I will be doing many many inserts, a lot of reads (to check if states (or equivalent states) already exist开发者_运维知识库), and very few updates.

Also, how can I parallelize it so that many clients can work on solving different branches without duplicating too much work. I'm thinking something along the lines of a program that checks out an assignment, generates a few million states, and submits it back to be integrated into the main database. I'm just not sure if something like that will work well, or if there is prior work on methods to do that kind of thing as well.

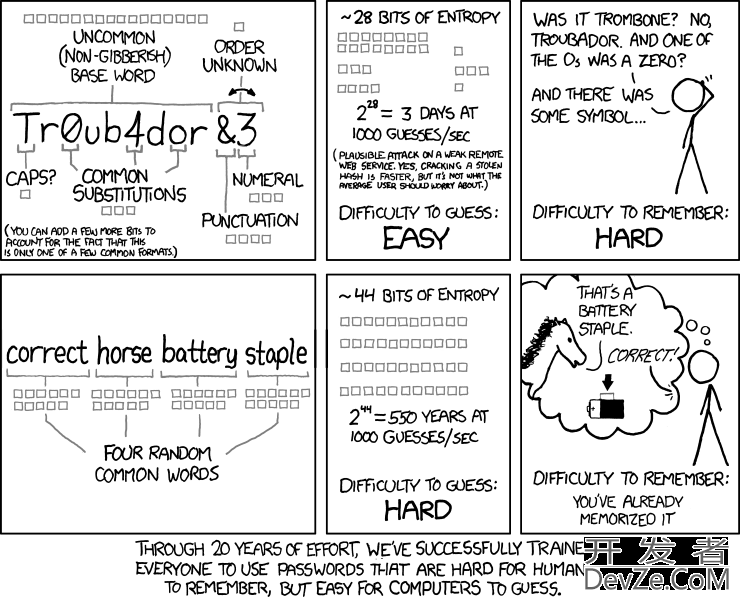

In order to solve a game, what you really need to know per a state in your database is what is its game-theoretic value, i.e. if it's win for the player whose turn it is to move, or loss, or forced draw. You need two bits to encode this information per a state.

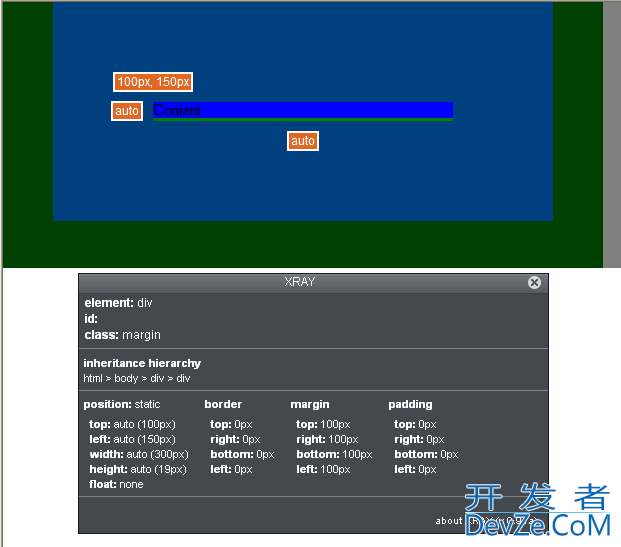

You then find as compact encoding as possible for that set of game states for which you want to build your end-game database; let's say your encoding takes 20 bits. It's then enough to have an array of 221 bits on your hard disk, i.e. 213 bytes. When you analyze an end-game position, you first check if the corresponding value is already set in the database; if not, calculate all its successors, calculate their game-theoretic values recursively, and then calculate using min/max the game-theoretic value of the original node and store in database. (Note: if you store win/loss/draw data in two bits, you have one bit pattern left to denote 'not known'; e.g. 00=not known, 11 = draw, 10 = player to move wins, 01 = player to move loses).

For example, consider tic-tac-toe. There are nine squares; every one can be empty, "X" or "O". This naive analysis gives you 39 = 214.26 = 15 bits per state, so you would have an array of 216 bits.

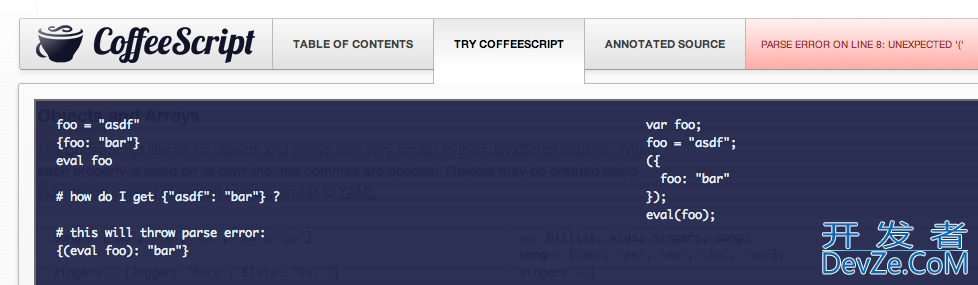

You undoubtedly want a task queue service of some sort, such as RabbitMQ - probably in conjunction with a database which can store the data once you've calculated it. Alternately, you could use a hosted service like Amazon's SQS. The client would consume an item from the queue, generate the successors, and enqueue those, as well as adding the outcome of the item it just consumed to the queue. If the state is an end-state, it can propagate scoring information up to parent elements by consulting the database.

Two caveats to bear in mind:

- The number of items in the queue will likely grow exponentially as you explore the tree, with each work item causing several more to be enqueued. Be prepared for a very long queue.

- Depending on your game, it may be possible for there to be multiple paths to the same game state. You'll need to check for and eliminate duplicates, and your database will need to be structured so that it's a graph (possibly with cycles!), not a tree.

The first thing that popped into my mind is the Linda-style of a shared 'whiteboard', where different processes can consume 'problems' off the whiteboard, add new problems to the whiteboard, and add 'solutions' to the whiteboard.

Perhaps the Cassandra project is the more modern version of Linda.

There have been many attempts to parallelize problems across distributed computer systems; Folding@Home provides a framework that executes binary blob 'cores' to solve protein folding problems. Distributed.net might have started the modern incarnation of distributed problem solving, and might have clients that you can start from.

![Interactive visualization of a graph in python [closed]](https://www.devze.com/res/2023/04-10/09/92d32fe8c0d22fb96bd6f6e8b7d1f457.gif)

加载中,请稍侯......

加载中,请稍侯......

精彩评论